Parshat Behalotecha begins with the commandment given to Aron to light the menorah in the Mishkan. Menorah is such a strong and central symbol in Judaism that much later in history it was chosen as the symbol for the State of Israel flanked on either side by two olive branches. This image was designed by Gabriel and Maxim Shamir, two brothers from Latvia, who studied graphic art and design in Berlin before making aliah; and they also created coins. The decision to surround it with olive branches is based on a vision of the prophet Zechariah in ch. 4.

The menorah was officially adopted on the 10th of February 1949 by the Provisional State Council, and it is easy to appreciate why a symbol was chosen for a nascent nation that spans the entire history of Judaism and the history of Hanukkah; images of menorot have been found at every site in the Land of Israel through the centuries.

But the choice was not without controversy. The design of the menorah depicted in the state symbol is of the same one that appears in the Arch of Titus in Rome, c.e. 81, commemorating the victory of the Romans and the conquest of Jerusalem. The panel depicts jubilant Roman soldiers with objects taken from the Temple, trumpets, braziers, the shulchan and in the center ... the menorah.

Chief Rabbi Erzog strongly disagreed with the choice since the design of the menorah that appears on the Arch of Titus is not the one of the Temple's menorah: according to the Talmud and Rashi, this one had a tripod base - as depicted in historical archaeological images - while the one on the Arch had a hexagonal base.

Another problem concerns the dragons and other mythological beasts depicted at the base: according to Rabbi Erzog, it is inconceivable that such creatures would decorate an object that stood in the Temple, as the use of such mythological creatures was prohibited by the Halacha.

So the design of the menorah of the Arch of Titus is not the same as the Temple's menorah. Instead Erzog suggests that something happened on the journey, perhaps the Romans replaced the original base with the hexagonal one. Erzog concludes that the current government of Israel did not do well, now that we have 'the light of Zion' again, to keep the image of the menorah of the Arch of Titus that was created by stranger hands and not in purity according to the Torah.

Indeed, archaeologists testify pre-Herzog that menorot found in catacombs, tombs, in mosaics and synagogues etc. always have tripod bases. Even sages such as the Lubavitcher Rebbe believed that the arms of the Temple menorah were straight and not curved, according to Maimonides' illustration.

It would seem then that the Shamir brothers foresaw this controversy, at least regarding the mythological beasts at the base, and obscured such images in the emblem of the State of Israel.

Nevertheless, the controversy even among the rabbis died down and in time for Independence Day 1 the image was accepted. Perhaps for some the very choice of the menorah from the Arch of Titus in Rome for the nascent state was symbolic and significant.

Indeed, for centuries the Arch of Titus represented the destruction of the Temple and of Jerusalem, and the long exile. But with Independence, that image took on a new life and meaning. Now, having rebuilt the state and returned to Jerusalem, Jews look to the symbol with a sense of victory and hope.

The menorah of the Arch of Titus appears in covers of books, monuments and religious art subsequent to the birth of Medinat Israel, and was adopted as a symbol by the Jewish state becoming a source of pride for us.

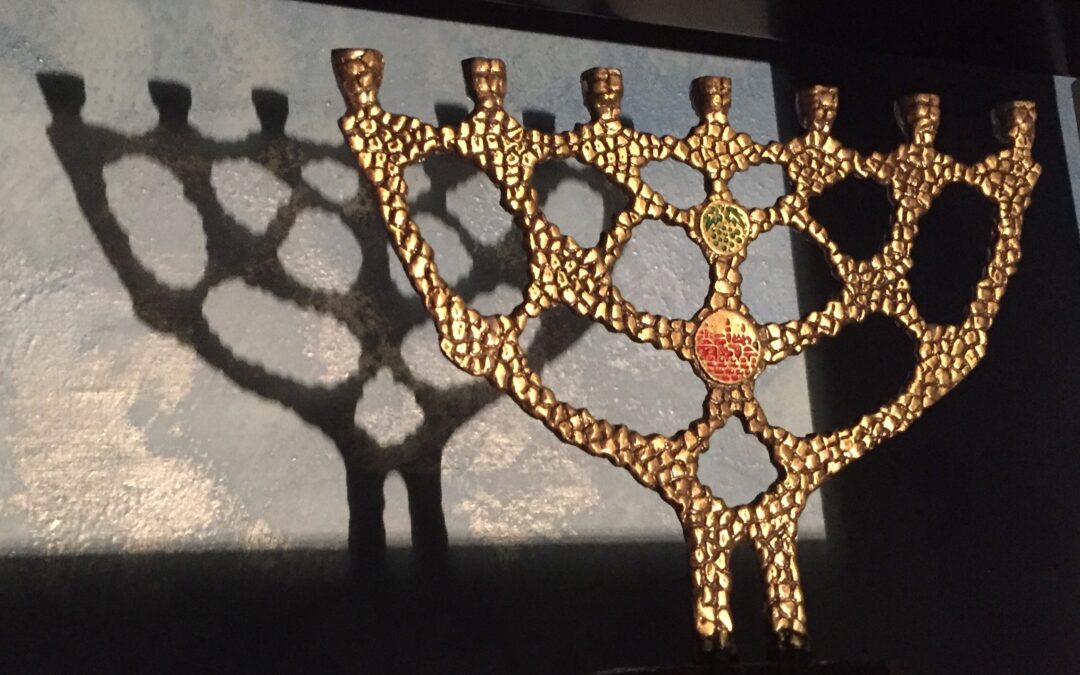

In the photo, a bronze menorah that I purchased in Israel in 2015 for my store in Modena. You can see the front decoration with enameled inlays, one depicting Jerusalem and above that with grapes, which is a very popular symbol in Judaism.